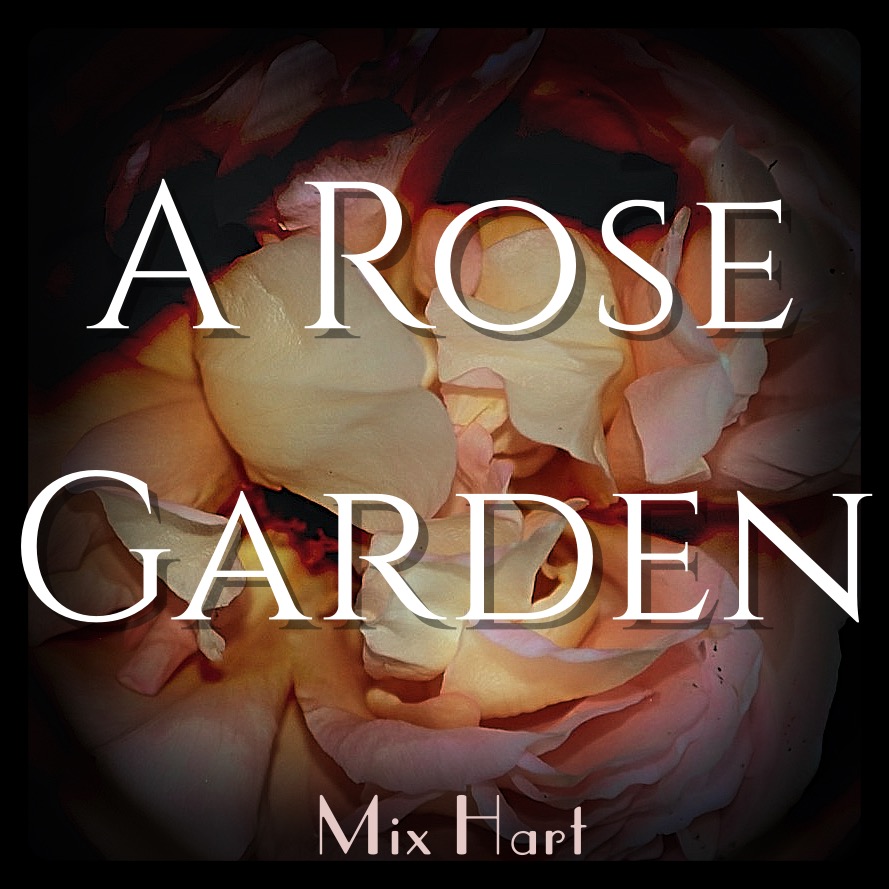

A Rose Garden

Chapter 3

May

It was peaceful on the mountain before the neighbourhood woke. A California quail patriarch called, “Chi-ca-go,” from the fence post, as his grown family searched the yard for breakfast. Inside the maple tree, a golden finch chirped to the scarlet finch that sat in the lavender bush. Elsa had been forced to wake early, so Hugo could fit the rose garden into his inflexible schedule. As always, the morning was intoxicating in its natural beauty and Elsa was once again determined to force herself out of bed by six for the rest of the spring and summer.

“This is the last one,” Hugo said. He seemed irritated, rushed, as though the garden was keeping him from something.

Elsa shoved in the brick and placed the level on top. “It’s good,” she said. She stood up and wiped her soil stained kneecaps. “I like it!” Elsa said as she admired the long, distressed bricks. “It really adds elegance to the front yard, don’t you think?” Grass had long ago jumped the plastic lawn barrier. The newly placed bricks protected a garden of Kentucky Bluegrass. Its long, uncut stocks hid the dead and dying rosebushes—all that remained of the original rose garden’s past splendour.

“Yeah, it does.” Hugo’s agreement resonated like a sigh of relief.

“All we have to do is pull out all the grass and then I can replant this baby,” Elsa knelt to inspect the newly purchased Abraham Darby rose bush—waiting in its pot, on the browned lawn, to be planted. “We should be able to smell the roses in our bedroom once it blooms.”

“I can’t. I’m going to head out to the field. I need to check on the undergrowth before the spring melt floods the creek and cuts off access. They still haven’t replaced the bridge.”

“Why? No one’s doing research. The labs are closed.”

“Why?” Hugo said. His voice was loud and higher-pitched than usual.

“Shhh, talk quietly. The neighbourhood’s still asleep. No one gets up this early except you.” When he got like this, acting as though his work held the secrets of the universe, Elsa was instantly repelled by his arrogance, and suddenly, she wanted him to leave—work or no work—just to be rid of him for the day.

“I missed my run so I could help you finish the bricks. I told you I was going to go out in the field today.”

“No, you said, this week sometime. You didn’t say today, specifically.” In truth, she couldn’t remember what he’d told her. She tuned out when he started to natter on about his work. In the beginning, she had listened to his ramblings, believing in the better future that his work would help build. Hugo’s research, on ungulate populations, was instrumental in lobbying the government to take a break from aerial spraying— in creating designer forests, they’d eradicated biodiversity, and all food sources for the herbivores. The forests had been sprayed with pesticides and herbicides—glyphosate and a few other chemicals—for nearly a decade, destroying the understory, and with it, all deciduous trees and plants, to ensure a forest of lodgepole pine—a logging industry favourite. You couldn’t call them forests anymore, they were monoculture tree plantations.

Although Hugo’s work gave much to the Earth, it took far more than Elsa was willing to accept.

Hugo left Elsa in the garden, along with the garden tools.

The tools were useless. The grass would not budge—the roots too long to pull out. She didn’t have the bulk and brute strength to permeate the clay beneath the thin top layer of soil. She’d have to dig up the entire bed—turn the soil upside down and shake the grass roots loose. The car doors beeped open. As much as she didn’t want Hugo to return to the forest, she was curious to know what he’d discover in “the field,” if he’d find evidence of biodiversity returning. It was the second spring without aerial toxins.

Elsa met Hugo in the driveway. “I want to go with you.”

“Are you ready? I have to go now.”

“I can’t. I have a meeting with a student in two hours…you could take Oscar. He needs a break from worrying about COIVD. It would be so good for him to spend the day in nature with his dad.

“Where is he, is he ready?”

“He’s in bed. You know he’s never up before ten since quarantine.”

“I can’t wait for anyone. I won’t have much time in the forest. I have to leave early, before the last ferry crossing. They have shortened hours since COVID—I’ll take him next time.”

“Will you be home for supper? It’s your night to cook.”

“Could you pick up takeout tonight? I won’t be back until 6:30 at the earliest.”

“What will you eat?”

“I packed a lunch—and I can pick up something in Trout Creek if I need anything.”

“Do you have bear spray?”

“Yeah.” He jumped in the car. She pantomimed rolling down the window—the old fashioned way, with a handle. Hugo pressed the window button and unrolled it halfway.

“Did you bring a mask? Wear a mask on the ferry and if you go into Trout Creek.”

“I’m not allowed out of the car on the ferry but I’ve got a mask. I’ll be fine.”

Elsa harnessed Leroy and headed out the back gate and up the trail, towards Rosa. She spotted a doe up ahead on a hill above the trail. She probably had a fawn hiding in the grass somewhere. Elsa left the path, taking the long route, through dense bush, around the side of the mountain. The deer stepped to the edge of the trail and watched Elsa and Leroy walking below. Elsa walked through the forest all year long, through the changing seasons, and the deer ignored her and Leroy—she’d even stumbled into the middle of a large herd on occasion, during dark winter morning walks. Spring was different—a post-natal doe will not tolerate a dog. Elsa walked quickly through the Saskatoon berry and Oregon grape bushes that covered the slopes. The deer trotted parallel to her on the trail above, keeping pace with them, her head held high and alert. The slope turned into a craggy rock escarpment ahead of Leroy. The deer had also come to the end of the trail above. There was nowhere for any of them to go but down, along the side of the rock, further into the forest. Elsa ran, pulling Leroy, who initially seemed confused as to why they were suddenly running down the mountain. The deer crashed through the bushes, charging after them. Elsa scanned the ground for loose rocks or large branches to use as weapons—she was too far to run home. She had to get to Rosa. The breadth of the tree would protect her from flailing hooves. She sprinted beneath the rock precipice until she reached the other side of the mountain and then she climbed straight up, grabbing roots and branches when it became steep. She reached the ancient ponderosa and stopped. There was no sign of the deer. Elsa braced herself against the side of the tree. She’d never run so hard in her life. She felt like throwing up. She collapsed beneath Rosa. Leroy licked her face nervously as she pulled a thermos of iced tea from her shoulder pack. She was shaking too hard to unscrew the lid. She leaned back on the bark, to catch her breath. The tree stayed with her or she stayed with the tree—she wasn’t sure which one it was until she felt that she was home.

Flora and Wyatt sat in the loungers on the front balcony, drinking coffee. Flora was wearing cut-offs and a bikini top. Wyatt was bare-chested and wearing—what looked like—Flora’s yoga pants.

“Any exams today?”

“No, not until next Tuesday, then that’s it, I’m done!” Flora said.

“Wyatt, you’re finished exams, right?”

“Yup.”

“When will you find out if the store will have work for you?”

“He already did. They’re staying closed—indefinitely,” Flora interrupted.

“Oh no. Are they closing down?”

“No. Online ordering is going okay—they’re selling a record amount of puzzles,” Wyatt said.

On closer inspection, Elsa saw that they were definitely Flora’s yoga pants. “Are those Flora’s pants?” Elsa asked.

“Yeah,” Wyatt said.

“He’s doing laundry—what happened to Leroy? He looks dead,” Flora said. Leroy lay on his side, flat against the balcony floor, eyes closed.

“We were chased by a psychotic mother deer and nearly killed—can you and Wyatt finish weeding the rose garden? All I need you to do is pull out the grass. It won’t take you long, half an hour max with the two of you working on it.” She left the silent two-some before they had a chance to think up a reason why they couldn’t do it.

Elsa flopped on the master bed, then sat up and untied her hiking shoes. She glanced at the clock and flopped down again. The post adrenalin exhaustion from the deer chase left her too depleted to move. Twenty-five minutes until the online session with her student started. She dreaded it. The girl’s mother hovered just off-camera as the girl sat like a silent zombie. Elsa closed her eyes and listened to the clang of metal against brick in the garden below.

“Where’s the garden? This is nothing but grass,” Wyatt said.

“Shut-up—just dig,” Flora said.

“This is gonna take a while—can’t we just spray it with Roundup and be done?”

“Roundup? Are you insane?”

Wyatt mumbled something. Flora answered in a hushed voice. Elsa sat upright, trying to hear what was said. “Glyphosate is what caused my dad’s Parkinson’s.”

“Sorry—really?”

“Yes—keep digging.”

“Like—how’d that happen?”

“He was in the forest doing fieldwork. A helicopter flew over and dumped herbicide near where he was working. It drifted into his forest. He said the smell was so bad, he instantly puked.”

Elsa remembered the night. Hugo arrived home covered in a bright red rash, and what appeared to be a violent gastrointestinal bug.

“He got Parkinson’s that fast?” Wyatt asked.

“No—that happened when I was in grade six, I think. He was diagnosed with Parkinson’s two years ago—I was grade eleven.”

“So, is he cured now? He seems healthy.”

“No. There is no cure. He manages it—takes pills every day to keep it under control—kind of like someone who has diabetes. So far he hasn’t have any physical symptoms. I’m hoping he never will.”

“They think it was the Roundup that caused it?”

“Glyphosate. Yeah—there’s nothing else it could be. My dad never smoked, he barely drinks…he’s been doing CrossFit since it was invented.”

The conversation shocked Elsa awake with a shot of residual adrenalin. It was not something she and Hugo discussed with the children, not since the initial diagnosis. Listening to Flora describe her father’s disease with such knowledge and calmness, gave Elsa hope that maybe the kids were okay and that perhaps, her decision—for herself and Hugo to tell the children an optimistic truth—was the right thing to do in a situation that had nothing right about it.

Oscar knocked softly on her bedroom door.

“Come in—good morning—how’s my baby boy?”

Oscar was dressed and his hair was brushed. “Can I hang out with my friends today?”

Elsa’s mind was still focused on the conversation in the rose garden. She smiled vacantly as she tried to refocus her attention on the boy in her bedroom. “Did you finish your schoolwork?”

“Everything except Tech Ed. But I don’t have to hand it in until June—can I hang out at Tyler’s?”

“In his backyard?”

“I don’t know—probably not. Everyone’s there already. They’re playing…video games.”

Oscar’s pause alerted Elsa that they were probably playing a violent video game that she forbid him to play. “Where are they playing video games, inside Tyler’s house?”

“In his family room. It’s in the basement—I can sit on the floor, six feet away from everyone.”

“Why aren’t they social distancing?”

“No one is.”

“We are!”

“They don’t have to because they don’t have a vulnerable person living with them.”

“What is wrong with them? I blame their parents—they are vulnerable. Look at your friend Will, he has horrible asthma—COVID would be really hard on him. And what about Tyler’s mom? She has diabetes. It’s not a given she’d survive COVID.”

“So, can I go?”

“I want to follow the government rules. They should be following the government rules.”

“It’s not fair. My friends hang out all of the time. I’m the only one who can never go anywhere.”

“You can go outside with them—talk to them online—play games with them online.

“No one goes online anymore. I’m the only one. They won’t even talk to me online anymore. They’re always hanging out with each other, doing fun things.”

“Do you try to talk to them online?”

“Yeah, I always do and they won’t even answer me. I’m left out of everything.”

“You went biking with them….why can’t they hang out outside?”

“They don’t want to go outside. They said they want to do indoor stuff today.”

“I don’t know what’s up with them. But your friends love you. I know they like hanging out with you—what about James?”

“Every day I ask him if he wants to do something but he never gets back to me.”

“They’re drips—I’m not impressed with the selfish little shits.”

“Mom! They’re my friends.”

“I’m sorry. You’re right. They’re kids. I’m just mad at their parents for being so bloody narcissistic and not quarantining. It’s not fair for the people who are following the government rules. It punishes the kids whose families are following the rules.”

“Can’t my friends be in our bubble?”

“They don’t live with us.”

“Why does Wyatt get to live with us?”

“Because Flora can’t be near him unless he’s in our bubble.”

“I don’t want to be in our bubble anymore if my friends can’t be in it.”

“I want you to be able to hang out with your friends. But what am I supposed to do? Your dad cannot get COVID.”

“Can I go if I wear a mask?”

“Not if you’re inside an enclosed space. Your dad has Parkinson’s for god sake!

You can’t bring COVID home. It could kill him!”

Oscar’s head slumped forward. She’d said too much. He buried his head in his crossed arms and his shoulders shook. Elsa bounded from the bed to hold him, expecting him to push her away but he didn’t. “I’m sorry I yelled. Your points are valid. I’m sorry I shot them down. I’m in a bad mood. I didn’t get much sleep last night.”

🌹

Hugo tiptoed into the bedroom, stripped off his clothes and crawled into bed beside Elsa. It was a notable occasion, the first night in recent memory that she’d beaten him into bed. She pretended to be asleep, too tired to conjure up the anger needed to address him. His breathing slowed and deepened. He was already asleep.

“Last ferry, my ass,” Elsa said. Hugo’s breathing remained slow and steady. “Where have you been?” she said loudly.

“They moved to summer ferry hours. I stayed as long as the sun would allow me,” Hugo said.

“You couldn’t answer your fucking phone?”

“No, I couldn’t. I was out of cell service until the ferry and then my battery died.”

“Convenient.”

Hugo rolled over, his back forming a wall between them. She was too tired to care anymore; though, she mustered up the energy to place a spare pillow firmly between them, strengthening the wall.

Parkinson’s wasn’t sexy. No one talked about that. The young lovers had suffered a blow that shook the relationship to its beginnings. Parkinson’s had aged their souls and frozen the love affair. They were holding back from emerging as old lovers, facing the inevitability of disease and death. It was a premature reckoning that neither was ready for.

Leave a Reply