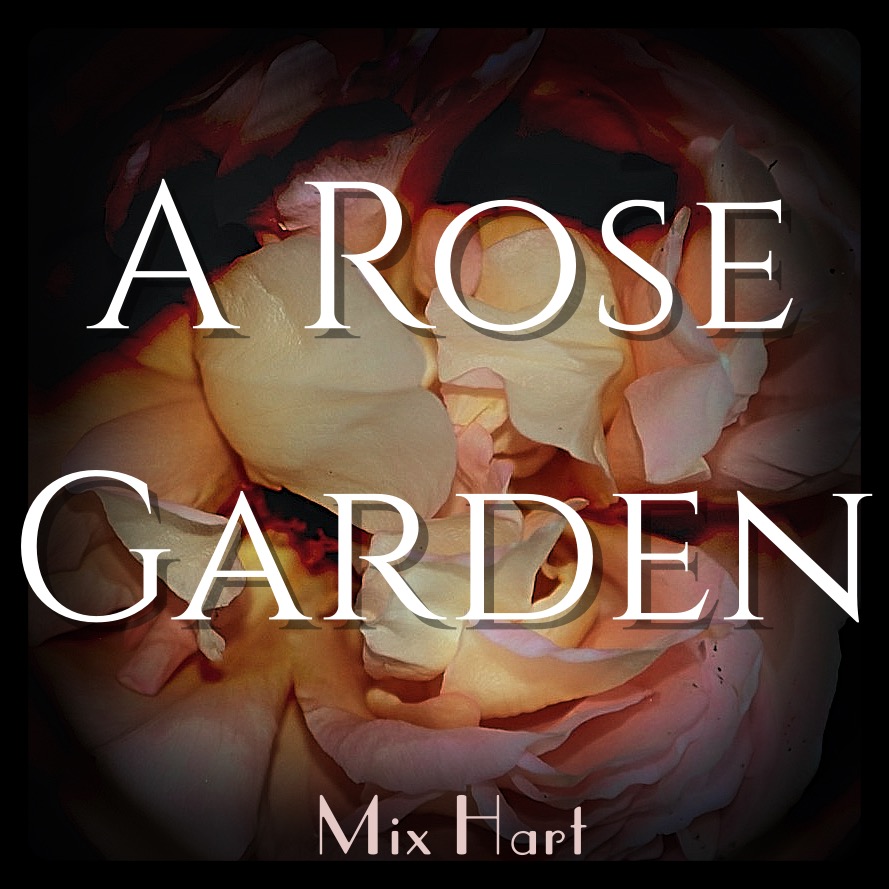

A Rose Garden

Chapter 5

Everything was dry. Elsa’s online counseling calls dried up. She was relieved, spared from imparting positivity and wisdom that she no longer held…Elsa had dried up too. The monotony as a mountain-top prisoner living in a cloud of toxic air had shriveled what was left of her sanguinity. She sat in the SUV beside Hugo, as he drove down the mountain to pick up take-out from Taco-Pogo. It was her first time off the mountain in three days.

The car smelled stale, like garlic and old cooking oil. Elsa traced the scent to her own pony tail. She couldn’t recall when she’d last washed her hair.

“I can’t move in with Wyatt,” Flora said from the back seat. “His step-mom hates me and no one in his family is social distancing—they all work with the public. His step-mom works at the hospital. His Dad works at the airport. His step-sisters go back and forth from Wyatt’s house to their dad’s house.”

“Wyatt’s working with the public, Flora. He can’t come back and live with us again—if you want to be in his social bubble, you’ll have to isolate from us too.”

“Didn’t you hear? I can’t live at Wyatt’s—what’s the point of anything? I’ll be trapped at home with my parents, unemployed, like some dumb-fuck gamer, for the rest of my life!”

“It’s only temporary. As soon as we have a few weeks with no new cases, things will be back to normal—look at New Zealand. You can still meet him for evening walks downtown. Leroy loves that.”

“What’s the point of that? It’s stupid. I’d rather not see Wyatt at all than to have to stay six feet away from him!” Flora shouted. “I don’t understand why Wyatt can’t come back if we move into the basement.”

Elsa regretted getting in the car. She should have stayed at home with Oscar and played another round of crazy-eights. “None of this is my fault. I didn’t bring COVID across the ocean. I didn’t spray the country with glyphosate and give your dad Parkinson’s—I’m trying to protect the family. That is all I am guilty of,” Elsa said, her voice rising in frustration.

“This is bullshit—you’re being horrible! I’m moving out! Stop the car. Stop the car, I want to get out!”

“Flora. It’s okay. You don’t have to move out. We’ll work something out,” Hugo interjected, calmly.

Elsa glared at his profile as he drove through downtown. He’d sat silent through the entire conversation, left her on the front lines alone, and then he decides to speak up, only to undermine her. “Stop the car—seriously, stop the car, Hugo! Flora can stay, I’m the one getting out—go home. I’ll walk.” Elsa closed the door with enough force to be dramatic without actually slamming it.

Hugo followed her slowly in the car. She walked in the direction of the mountain. “Get in Elle. You can’t walk home. It’s not safe for you to be in the smoke with your asthma,” Hugo said, in robotic calmness. She crossed the street. “Elsa!” Hugo called in frustration.

Hugo was right, climbing the mountain in the heat and smoke would hurt her lungs. It would take her close to two hours on a clear morning. Tonight, in the heat and smoke, she would be out until past sunset. She didn’t have her inhaler or her phone, but there was no way she would willingly get back in the car. Flora’s intolerable sense of entitlement and Hugo… it was too much. Elsa glanced behind. Hugo made a U-turn and drove away, in the opposite direction that she was walking. Certainly, he could see that she’d left her phone in the car! Elsa knew that she would never abandon someone in the heat and smoke, near sunset—even if she hated them. She walked past a minuscule corner store with a neon Orange Crush sign. It looked half a century out of place, somewhere she would have stopped at to buy penny candy in her childhood. Thank god she hadn’t washed the thin hoodie she had tied around her waist—it still held the change from the twenty she’d given to Oscar for the ice cream truck weeks ago. A little bell jingled from above as she slipped inside the door. She didn’t need caffeine, her anger at Hugo was fuel, but she purchased a bottle of iced coffee to be safe.

Hugo never backed her up in front of the children—he either remained silent or coddled them. Flora was a princess but it was the fault of the ineffectual king who lived within the barriers of his own grief…and Elsa—the matriarch who’d been trying to hold the jalopy of the family together since the Parkinson’s diagnosis and beyond, through the COIVD nightmare—was crumbling along with her queendom. She reached what she knew to be the base of the—now invisible—mountain and walked along the shore of the shrouded lake. At least the path was relatively flat, saving her lungs for the climb that she knew was coming. The sky was sunless. The only hint that the massive fireball existed was that its flames turned the smoky sky an alien, Mars-orange. Elsa reached the trail that led to Rosa. Upwards she climbed, through dust-dry dirt and loose rock, until her sport sandals slipped backward. She scrambled up, holding onto branches and roots, pulling herself along the goat-like trail. Her lungs shut out the soot, making it impossible to take a deep breath.

The climb was reckless. She knew how dangerous smoke particulates were. They entered the blood through the lungs and clogged the hearts of even the healthiest athletes. She glanced at the trees within view, finding comfort in the orange-striped older trees’ bark. The mature ponderosas were beacons of calm—matriarchs in a sea of smoke. If she needed, she’d stop and catch her breath beneath the ponderosas. With their support and the iced-coffee, she could make it to the top.

The coffee bottle was empty by the time she reached Rosa. The orange sky had turned slate. Soon she’d be in complete darkness. Even a harvest moon would not penetrate the smog. Elsa sat at Rosa’s base, closed her smoke-irritated eyes, and coughed to clear her lungs. “The queen has fucked up,” she said. Elsa knew that Flora’s entitlement was partly caused by her own fear of setting limits for the children. Hugo’s Parkinson’s diagnosis, then COVID, and now, living in a lifeless smoke void…so many reasons to go easy on the kids, to not add any more stress to their young lives. Yet, maybe, slack boundaries were not what they needed…. Regardless, Elsa had stepped down from her throne—allowed disease to invade her world and dictate her life. The disease wasn’t Parkinson’s, Parkinson’s was a symptom. Disease festered within the government and spread through the designer forests they created. The smoke that shut down her life was not caused by natural forest fires, but firestorms: designer forest infernos—first growth, matchstick trees. There was nothing left to slow the fires. The old-growth had all been logged, water-heavy deciduous trees forcefully eliminated. The only trees remaining were young, pine or fir—standing like a box of match sticks, waiting to ignite. Their fires burned so hotly, they were unstoppable, incinerating everything in their path. Nothing could regenerate once a new growth forest burned. It was a country, a continent, a world, of designer forest plantations. There was no understory in a designer forest. Helicopters sprayed poison to make sure of it. Poison that invaded every living thing within miles—poison that had leached into Hugo, attacking his life, and then moving through his family, the collateral damage of its toxic trail.

Rosa was old growth. She didn’t burn. She was all that remained of the forest matriarchs. The others, long gone—ground into toilet paper for an international array of asses. “I will be like you, Rosa—I will not burn,” Elsa said.

🌹

Streaks of sun fell onto the bed and across Elsa’s face. The sky between the shutters was cerulean. She sprang from bed and rushed onto the balcony. The wind had shifted, blown the smoke back whence it had come. A symphony of birds celebrated the pristine air. It was a shock after days of silence. Each breath of clean air felt like a miracle. She recognized the small corner of the lake, miles below, and the trees on the mountain behind the house. She harnessed Leroy and slipped through the back gate.

The balsamroot silver-green leaves crackled like rustling paper as Leroy brushed them side to sniff at their base. The entire mountain was illuminated in sunshine-yellow, balsam-root flowers—the flowers showed signs of wear. Elsa had missed their spring debut—the smoke had concealed all that was beautiful. Elsa reached the giant ponderosa, embraced her robust friend, inhaled her vanilla fragrance, and then took a seat in the long, crispy, brown needles at her base. She leaned against the tree. Relief flowed from Rosa into Elsa. The fresh air had caused such excitement that she’d forgotten to pack a thermos of tea. She scanned the forests beneath them, from her high vantage point, she could pretend the mountain wasn’t dehydrated. She saturated her mind with the impossibly blue sky, the deep azure lake, and the canopy of moss-green ponderosa tops, and the darker, emerald firs. If and until the smoke returned, she would not waste a moment of the clean air. She would rise before six, for the rest of the summer, to fully embrace the miracle that was a morning on the mountain, simply breathing.

The doorbell rang. Leroy lost it, bolted down the stairs, and barked ferociously at the front door. “Kennel!” Elsa called. Leroy paused his barking momentarily. “Kennel, Leroy, Kennel!” She repeated in an artificially low, and slow intonation. Leroy sunk his head between his powerful shoulders. His nails tapped as he ascended the staircase. He trotted into his kennel and then lay down in a defeated sigh. Elsa locked him in the kennel and then walked onto the balcony and gazed below, at the front door. It was the neighbour, Richard. She hadn’t seen a trace of him since COVID hit, although she continued to smell him. “Hello?” Elsa called. Richard looked around, disoriented. “Look up,” she said.

“Oh, hi—I just stopped by to let you know that there’s a fire on the mountain. Cops asked me to alert the immediate neighbours, to get the message around, in case we have to evacuate. ”

“Are you serious? Where?”

“They said it’s on the other side of the mountain, near the lake. The wind is keeping it down low, along the shore, but if that changes, we could be in trouble.”

Elsa thought of Rosa.

Flora ignored her mother’s call. Elsa called again, resisting the urge to storm into Flora’s room. Surely, the urgency in her tone would stir Flora’s curiosity.

“I’m in my room,” Flora said, in a bored voice, only just loud enough to be heard. Elsa didn’t have time to play games. She rushed to Flora’s room, knocked once, and opened the door. Flora was scanning rental properties on the internet despite not having an income.

“There’s a fire on the other side of the mountain. I texted Dad to come home. Can you text Wyatt to come over too? We need to gather photos, computers, art, small antiques. We’ll store them in boxes in the garage in case we have to take them down the mountain.”

“Wyatt works until five. Why can’t Oscar help?”

“He can, but he’s so afraid of fires. I don’t want to say anything to him—yet—let me tell him if the time comes.”

“Where is he, anyway?”

“He’s paddle-boarding with the fab-four. Someone has to drive down to Tugboat Beach at five and pick him up. I hope he can’t see the fire from the lake. He’ll freak.”

Elsa texted James’ mom, to ask her if she could pick-up Oscar—and his board—and take

them to her place. Through her side gaze, she saw Flora haul a large suitcase into her bedroom. Elsa’s phone pinged. She peeked into Flora’s room and said, “Oscar doesn’t need pick-up—he’s going to James for supper.” Flora was focused on gathering items from her closet in—what seemed to Elsa to be—slow-motion speed, as though she was causally packing for a vacation. Elsa sped through the house, gathering the things she had written on the list in her brain that she’d edited on smoke-filled nights when she was unable to sleep.

Wyatt arrived in his father’s car, his first time back since he’d moved out. Flora met him on the driveway. A plane rumbled overhead, so close to the house that Elsa could see that the pilot was wearing sunglasses—a water-bomber, carrying a huge bucket of lake water to dump on the fire. “Where is your father—he said he’d be right home!” Elsa snapped. She led Wyatt into the open garage, to the underground sprinkler panel. “Put them full-on, indefinitely. We’ll give everything a good soak tonight. We’ll keep things wet until the fire’s out.”

“I can’t believe Oscar hasn’t called or texted in a panic over whether or not he’s allowed inside James’ house,” Flora said.

“Yeah,” Elsa said, distracted. The water bomber flew over again, on its way back to the lake to refill its bucket.

Wyatt’s father’s car was parked in the drive so Hugo parked on the street. He attempted to slip in through the front door unnoticed, and disappear, undisturbed, somewhere inside the house until supper time. Elsa hustled through the garage side door and met him at the entrance.

“What took you so bloody long?” She didn’t wait for the excuse that he was forming. “I need you to drive the first load of in-valuables down the mountain to store in your office.”

“I can’t right now,” he said and slipped past her to the staircase.

“What do you mean, you can’t?”

“I will—if we have to evacuate.”

Hugo’s doubt added to Elsa’s burden but she didn’t falter. She trusted her instinct when the safety of her family was concerned. She saw things that others didn’t—the big picture, but also all the little details. She wasn’t even fully aware of all that she took in. It was processed in the realm of her subconscious and was communicated to Elsa through her intuition. What others didn’t have, they couldn’t comprehend.

The wind changed. Wyatt and Flora led the line down the mountain in his father’s car. Leroy rode shotgun in the convertible with Elsa, and Hugo brought up the rear in the SUV, packed pressure-cooker tight.

COVID travel restrictions meant that the campground was unusually quiet. A sign

at the entrance warned of a grizzly roaming the campground earlier that week. The children insisted that they pitch the tents near the riverbank, with only a patch of thimbleberry bushes between the tents and the water’s edge. Elsa didn’t discourage it, yet she secretly wondered if they’d have to move them once darkness fell on the sparsely populated campground and anxious minds made the connection between berry patches and grizzly bears.

“Is Oscar still at the toilet?” Elsa asked.

“He’s okay. He’s got Leroy with him,” Hugo said.

“Can you go check on them?”

“I see him on the road. He’s coming.”

“I counted—only thirteen sites are taken,” Oscar shouted from the road.

“How many sites does it have in total?” Elsa asked, once Oscar reached their driveway.

“We’re in number seventy-nine, and there’s about eight more after us—so probably about

ninety,” he said.

“It’s less than a quarter full. No wonder we snagged a site on the river bank.”

“This is so cool!” Oscar said. “We’ve never been able to get a campsite on the river before.”

His face was animated with youthful exuberance. It was the Oscar that Elsa remembered from before COVID. “It is a real treat. I’ve never been able to book one in time. I guess there are some perks to COIVD,” she said.

Hugo walked the serpentine campground road. His cell phone was periodically glued to his ear or held high above his head as he squinted at its screen. Elsa knew from past experience, that cell service at Blanket Creek was sketchy, but it was the only place that she and the children were willing to go; it was the campground they had tented at each summer since the children were babies. Elsa found comfort in the old-growth cedar and towering hemlocks. She placed a camp chair in the space between Flora and Wyatt’s backcountry tent and the family tent, just beyond the shade of a grand cedar but close enough to inhale its calming scent. She turned the chair so that she could catch views of both the river and the kids playing volleyball on the dirt road. Everything was green. The oxygen-heavy temperate rainforest air felt to Elsa like an almost tropical escape from the arid smoke at home. Happiness had returned to Flora; she’d been beaming since Wyatt’s father had dropped him off. Leroy’s head bobbed from side to side as he watched the ball for a moment. He grew either bored or dizzy and sauntered towards Elsa’s chair and then flopped down at her feet. Elsa opened a paperback that she’d been trying to read since lockdown. With Hugo and his pacing out of view, she eased into a blissful, dog-day of summer—temporarily forgetting the reason that they were there.

Leave a Reply